From time to time, when I run across links of interest, I’ll post them. Those kinds of posts may be called “potpouri” posts… if I’m consistent about it…. which I may not be. Lemme alone, I’m a musician.

At Life and Art:

“through good theology and a little creativity, Jazz music can really help in faith integration issues. For example, by its very history, Jazz can serve to help reconcile racial relations. Also, due to its rhythmic nature, Jazz can involve the body and help fight that Gnostic mind/body split that exists in contemporary Christianity. Jazz is immediately accessible. Jazz can help correct that tendency of privatization in worship. Like Black Gospel music, Jazz has that ‘Call and Response’ element. Jazz is individual yet communal and it calls one to participate.”

Hmm.. apparently not everyone believes jazz is the devil’s spawn.

Spiritual “muzak” at the Institute for Christian Thinking:

“In order to further encourage this intentional promotion of faith, campuses can include facilities such as a prayer garden, a prayer chapel, quiet spots of natural beauty on campus, and by strategically-arranged park benches that provide places for quiet reflection. This faith perspective can also be enhanced by the selection and piping in of spiritually-uplifting background music in appropriate places (e.g., in recreation areas, lounges, etc.), and by the promotion and utilization of visual media programs (e.g., overheads, slides, TV, videos, etc.) which uphold and inculcate values congruent with the philosophical objectives of the institution.”

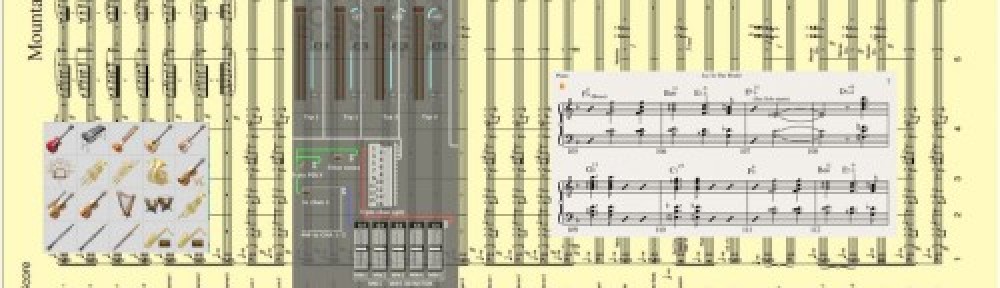

It’s not all about CCM… or at least it’s not all pop oriented. Check out the Christian Fellowship of Art Music Composers.

Their self-description:

“CFAMC provides a non-denominational forum for information and dialogue about activities in art music composition by professing Christian composers, as well as professional and spiritual encouragement for its members. Member services include a quarterly email newsletter, “the CONCERTed offering”, periodic conferences, a substantial web page, and a free, public email discussion group. Other endeavors include online composer catalogs, networking with major musical organizations, regional CFAMC chapters, comissioning programs, student composer scholarships, recording and broadcast projects, and much more! In short, CFAMC strives to be a place for evangelical concert composers to come together to discuss the joys and disappointments, the issues and struggles of bringing their work and witness as redeemed creative individuals to the arts music world. ”

On the surface this appears to be less of a faith integration organization, and more of an evangelistic one, with overtones of mutual support and community.

These are all good things, of course… but offer no window into how a composer’s faith perspective changes the way the music is written, except perhaps in matters of text selection, or the “program” of a piece. Question: will anyone be able to tell, by listening, that any piece of music was written by a Christian?